A few hundred years ago, sugar was essentially absent from the human diet. Today, according to the New York Times, it's "used in approximately 75 percent of packaged foods purchased in the United States."

The average American consumes anywhere from a quarter to a half pound of sugar a day. If you consider that the added sugar in a single can of soda might be more than most people would have consumed in an entire year, just a few hundred years ago, you get a sense of how dramatically our environment has changed.

In excess, sugar is terrible for our bodies, and when it's in 75% of all our food and drinks, we're definitely eating it to excess. It contributes to obesity, hypertension, diabetes and host of other illnesses.

So why do food manufacturers continue to inject sugar in everything from ketchup to pasta? Because it's addictive.

Your diet is part of an industry determined to maximize its profits. Manufacturers know if they add sugar to a product, it will taste better and leave you wanting more. Some research indicates sugar is eight times more addictive than cocaine.

And worse, manufacturers don't even use real sugar. They sub in high-fructose corn syrup, which is widely considered worse than sugar, at a fraction of the cost. Your body is being sold off for a profit.

If sugar was only added to a few specific foods, it wouldn't be so bad. Those treats would taste great and make manufacturers plenty of money. The problem is that the idea caught on and now, instead of getting a sugar rush from just one or two foods, we're getting sugar in almost every single food we eat.

The effect is that it's almost impossible to buy anything -- even a jar of mayonnaise -- without added sugar. As a result, according to the National Institutes of Health, 69% of American adults are either obese or overweight.

In the same way that food manufacturers have turned all foods into junk food just for the sake of customer retention, marketers are preying on the weaknesses of their users with habit-forming strategies and excessive notifications.

I say this at the risk of great irony. I work in marketing. This is my career, and I love it. But I feel compelled to put this out in the open: It's something I believe we should reflect on before triggering another push notification.

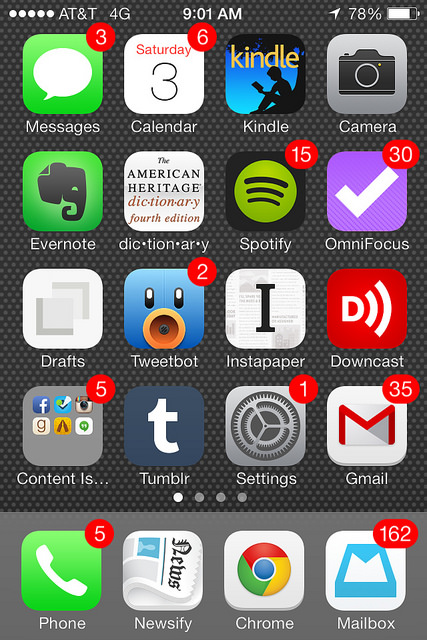

Image: Michael Coté

On one hand, behavioral experts like Nir Eyal teach companies how to build addictive mechanisms into their products. Nir's work is fascinating, and I, like many others, really respect him. He's incredibly smart, and I've used his blog as a resource many times in my own work.

On the other hand, you have people whose personal lives suffer as a result of the anxiety and exhaustion caused by too much technology.

Here's a quick excerpt from Nir's post Hooking Users In 3 Steps: An Intro to Habit Testing:

The truly great consumer technology companies of the past 25 years have all had one thing in common: they created habits. This is what separates world-changing businesses from the rest. Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Twitter are used daily by a high proportion of their users and their products are so compelling that many of us struggle to imagine life before they existed.

Herein lies the challenge for marketers: Nir is 100% right. These companies changed the game. Their products make our lives easier and better in many ways. But there's a good reason these companies went to great lengths to create habits — it's great for business.

As Bill Davidow wrote in The Atlantic:

Many Internet companies are learning what the tobacco industry has long known — addiction is good for business. There is little doubt that by applying current neuroscience techniques we will be able to create ever-more-compelling obsessions in the virtual world.

And just like the sugar industry, and the tobacco industry before it, there are victims in this game.

Habit-forming technology manifests itself in social media, email marketing, push notifications, retargeting ads, notifications and alerts. Users check their smartphones and other devices constantly, and each little bit of information triggers the release of dopamine. It isn't just a habit. It's truly an addiction.

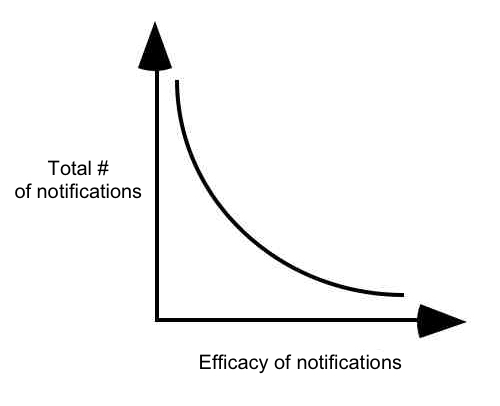

If just one company did it, they'd be rewarded with higher engagement and increased customer lifetime value. But when everyone does it, users are easily overwhelmed. Remember, it's not just your notifications buzzing on their phone — their attention is being pulled in a number of different directions.

Many tech companies have doubled down on notifications because of the competition for attention. The result is the equivalent of high fructose corn syrup in your peanut butter.

Our society is becoming technologically obese.

One implication of overload is ignorance, but tech addiction can cause more serious problems. A study from National Center for Biotechnology Information noted that, "Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) ruins lives by causing neurological complications, psychological disturbances, and social problems."

What the hell should we do about it?

If this is your first time visiting this site, you'll see two notifications asking you to join my weekly newsletter. The irony of that is not lost on me.

I write this post because we marketers need perspective. Not every product or service needs to be "sticky" to be valuable to your customers. There's a difference between building a valuable product and exploiting habit-forming technology to get attention.

As marketers, we need to be aware that our actions have implications, not all of which can be measured with analytics tools. Our engaged users are real people -- spouses, significant others, parents, family members and friends -- who are spending their precious time padding our bottom lines.

Just as we're rewarded for the problems we solve, we need to be accountable for the ones we create. Otherwise, we're no better than the executives who make the data-driven decision to add more sugar to the ketchup.

S/O to Amanda Russell for editing this article.